The #BlackLivesMatter movement which causes one group in society to feel inferior to another has caused many to question the use of cultural and religious icons. Black Lives Matter is an organized movement originating in the United States advocating for non-violent civil disobedience in protest against incidents of police brutality against African-American people.

There is a big global discussion about removing statues of persons who were involved in the transatlantic slave trade and who were seen as having promoted white supremacy. The Archbishop of Canterbury and the honorary head of the Anglican Communion on the BBC Today Programme on June 26, 2020 said that the church should reconsider its portrayal of Jesus as a white man. This has sparked much discussion about the use of culturally relevant icons in Church and Christianity. The Archbishop affirmed that “many Anglican churches did not portray Jesus as white” and that “Jesus is portrayed in as many ways as there are cultures, languages and understandings.”

Culturally relevant images have been used from the beginning of Christianity for example the symbol of the fish forming the word Christos, meaning Christ, which helped Christians identify each other. The cross, the dove, the shepherd were all symbols in the early church pointing to God, by those who chose to reflect on their significance.

Icons were widely used up to the Reformation. They were very important in the Middle Ages and in times and places where persons were illiterate, as the pictures, friezes, or sculpture would tell the story. Thus, Biblical stories, and the Sacraments could be found on the walls of ancient cathedrals. They are still being represented in our stained-glass windows and in the drawings of Mary, Jesus and the Saints.

An icon is a religious work of art, which depicts, Jesus, Mary saints or tells a biblical story. These icons are not worshipped but when viewed, should bring into focus the presence of God and point persons to some truth about God. These icons were sometimes used to teach and assisted in developing piety as they were reverenced when persons encountered them. Reverencing or venerating is honouring, which is not the same as worship. We worship only God. We however honour the things of God, things we consider sacred and treat them distinctly different from other things as they point us beyond themselves to God. Even in Judaism, there were paintings and other artistic representations such as cherubims (1 Kings 6: 27) and bible stories which were used for the same purpose.

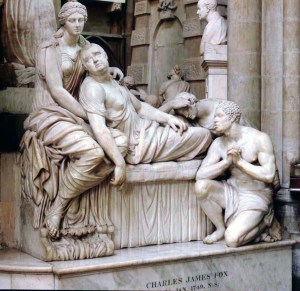

Westminster Abbey, England, which has a statue of Martin Luther King at its entrance has, in the Statesmen’s Corner, a black carving as a part of weeping figures surrounding the statue of Charles James Fox (1749-1806). Brooke-Hunt (1902) says Fox “powerfully championed” the ‘negro’s’ cause. The monument (Figure 1)

by the sculptor Sir Richard Westmacott, was installed in the Abbey in 1822. It shows “the dying Fox resting in the arms of a female figure representing Liberty. A slave (or perhaps a freed slave) kneels at the deathbed – the kneeling posture has been taken to represent both mourning and gratitude in reference to Fox’s support in Parliament for the cause of the abolition of slavery. The female figure behind the kneeling man (partly draped over Fox) represents Peace.” (Tony Trowles 2020). At St Margaret, Thrandeston in Suffolk there are corbels of a “negress” (Figure 2) and a “Moor”.

Black cultural images have also been used locally for a long time. At The Cathedral of St. Jago de la Vega in Spanish Town, corbels were placed on the building when the new Chancel was erected circa 1849-1853. Two of these corbels are black persons representing the newly emancipated ‘negro’. Thus, the Church has recognized the importance of other ethnic groups and the dignity of all persons.

In Jamaica, traditionally, the churches which use icons (ikons) have been the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, Roman Catholics and Anglicans. Icons used are of Jesus, Mary, other religious figures, and Bible stories. They have been portrayed as black by several artists and it is understood that they are not to be white.

In several Anglican Churches there are black icons or representations of Christian stories. Several Churches use black or culturally relevant images on their bulletins/newsletters. Most of these were commissioned in the 1970s, an era of heightened black awareness, pride and in the words of Prof. the Hon. Rex Nettleford, the ‘smaddytization’ of Jamaicans. These icons were all created by local artists.

Known Black Icons

The pieces of art mentioned here is not an exhaustive list of black icons in the Diocese. Some of these works were controversial at the time of erection. One such piece is the crucifix at St. Jude’s, Stony Hill, by Christopher Gonzales (Figure 3) below:

In 1973 Bishop Alfred Reid, then the Rector, commissioned a crucifix for the new Church. It is customary in an Anglican Church to have a cross behind the Altar. This one is more of a resurrection scene. The bird at the top represents the Holy Spirit, commonly expressed as a dove. In this work it is represented as a figure looking more like a screech owl (Barn Owl). Even Jesus’ image is controversial.

In 1973 Bishop Alfred Reid, then the Rector, commissioned a crucifix for the new Church. It is customary in an Anglican Church to have a cross behind the Altar. This one is more of a resurrection scene. The bird at the top represents the Holy Spirit, commonly expressed as a dove. In this work it is represented as a figure looking more like a screech owl (Barn Owl). Even Jesus’ image is controversial.

Rev. Khan Honeyghan, the current Rector, explains: “Jesus is coming out of the grave. He is triumphant and his hands go up in the air and it joins with the wings of the Holy Spirit. Jesus is a black man with broad nostrils, his hair and beard looking more like a Rastafarian. The ripple effect on the sides represent bolts of lightning as he emerges from the grave, representing the significant and powerful event of the Resurrection. There is a snake on the left. At the bottom are two heads. One immediately below Jesus and another on the right representing the people. Jesus is pulling out of Hades with him.” Persons objected to the imagery of the ‘Rastafarian’ Jesus and the dove looked ghostlike, they contend. St. Jude’s has several other black icons such as:

- “Black Jesus”, signature of artist illegible

- Mary, Joseph and baby Jesus fleeing to Egypt

- Black St. Jude – Barry Watson

- Mary – Barry Watson (Figure 4)

At The Church of St. Thomas the Apostle, commonly called The Kingston Parish Church, there are 3 pieces:

• ‘Piet’ by Susan Alexander – A triptych (Figure 5)

• “The Angel”, by Edna Manley and

• “Mother and Child” – Osmond Watson

The ‘Piet’ depicts the women anointing the body of Jesus for burial, and the ‘Mother and Child’ are currently located in the Lady Chapel.

The Church of St. Mary the Virgin, which was pastored for forty years by Liberation Theologian Canon Ernle Gordon boasts two Marianne figures, and a depiction of the Resurrection by Barry Watson.

Karl Parboosingh’s last artistic work is a mural behind the Altar at the Church of the Resurrection in Duhaney Park, Kingston. For some time, this was covered as members of the church community objected to it.

In At All Saints’ Church, West Street is a sculpture “The Crucifix” by Edna Manley which hangs over the Altar. In 1976, Neville Alexander gifted the newly built Church of the Holy Spirit, Cumberland, Portmore with a painting “Jesus” which stands behind the altar. (Figure 6) Painted by his wife Susan Alexander, Neville presented it on behalf of his faithful employee, Enid Brown.

The Church of the Transfiguration in Meadowbrook, boasts a stained glass window with black figures in it. (Figure 7) This was done by Mrs. Charmaine Thompson, the wife of Bishop Robert Thompson.

Other known images are:

• ‘Christ Ascending’ – St Andrew Parish Church in the All Souls’ Chapel

• The Chapel of Intercession – at the United Theological College of the West Indies, is a painting by Edna Manley

• ‘The Real Last Supper’ at Hillcrest Diocesan Retreat Centre.

• A statue at the entrance in the Chapel at The University of the West Indies, Mona

It is important to note that it is not only in the Anglican Church that bible stories or biblical persons have been depicted as black. The Holy Trinity Roman Catholic Cathedral has black saints in its stained-glass windows. Mallica “Kapo” Reynolds of the Revival Church is well known for his depictions of biblical stories using black people. The Rastafarians have always depicted Jesus as black.

Reasons for not recognizing Jesus as black

A lot of work has been done depicting Jesus and biblical characters as black, but we have chosen not to pay attention. The reasons may be many. Among them are:

-

-

-

- We have failed to understand that theology is contextual. Each person and each culture experiences God differently and we have allowed others to teach us or to suggest how God should be experienced. As a people we bought into a “correct” way of worshipping God and a “correct” way of practicing faith. That right way dictates a white God. We have failed to assert or even acknowledge our African heritage which is one of the main reasons for our failure to appreciate that Jesus can be black like us and that God has no colour or gender except those we give to God in an effort to better help us understand God’s action in the world.

- It may be that we have been brainwashed or indoctrinated in white supremacy and privilege. Many of us are still in a place where the higher one’s skin tone is perceived to be, the better you are as a person and so should enjoy better opportunities. There is a story of a European artist painting The Last Supper and using a young handsome man as Jesus. Several years later he wanted to depict Judas. He went into the prison and found a man whom he thought represented Judas. In time he realized that his Jesus had run afoul of the law and he had chosen him to be Judas.

- Many of us have been cultured to believe that anything black cannot be good and is therefore unacceptable. In the 1930s, the congregation at All Saints Church, West Street in Kingston rejected Canon Walter Brown, its first black rector. The Bishop told them he would not be assigning another priest, so they were forced to accept him. In 1783, George Leile (also spelt Lisle), a former enslaved African American, came to Jamaica and established what we know today as the Jamaica Baptist Union. The East Queen Street Baptist Church was dedicated 1822 to yet its first black pastor, Rev Leo Rhynie, who was only appointed in 1958.

- Perhaps, for us in Jamaica since we were taught Christianity by white persons who had indigenized Christ in their culture beginning with Leonardo DaVinci’s “Last Supper”. This made Jesus reflect their white self. We then acquired their thinking of Christ without developing our own. White Jesus is everywhere, on Christmas cards, on easily accessible imported photographs, the pictures which hang in our grandma’s home, and the free calendars given as gifts every December. Some of us have never really given thought to the colour of Jesus. Few of us would ever question these depictions. Others have refused to think differently particularly since our theological focus has been on our sins and our unworthiness. As we struggle to keep ourselves from hell, we think of nothing else.

-

- We learn our values vicariously from what happens around us, pictures, movies, our friend’s worldview, and the same happens in religious circle. How we view Jesus matters, as this determines how we view persons who are different from us. Every tribe and nation can make Jesus their own as each was made in the likeness of God. Further, the incarnated Jesus reflects each of us as we are with our idiosyncrasies. When we acknowledge this, then each person, people, race, and community can be proud of who they are. We can then be comfortable in our own skin, and also give to each other the respect and dignity each deserves.

-

REFERENCES:

Brooke-Hunt, Violet. (1902), The Story of Westminster Abbey, London. James Nisbet & Co. Ltd.

Please note that this article was prepared with the generous assistance of:

• Mr. Tony Trowles, Westminster Abbey, London, England;

• Reverends. Khan Honeyghan and Leslie Mowatt

• Dr. Trevor Hope, Mr. Bill Poinsett, Mrs. Margaret Mais,

Amateur photography was contributed by these persons: Rev. Khan Honeyghan, Mr. Bertram Gayle, Dudley McLean, and Herschel Ismail.